In 2013, Google former vice-president Amit Singhal projected the company’s vision for the future developments of one of their most popular services, Google Maps: “A perfect map of the world is foundational to delivering exactly what you want, when you want, and where you want it”. In the age of big data, Google Maps has created and controls a digital matrix closely interlinked with reality. It has the power to shape not only our perceptions but also the real world.

We take them for granted but digital mapping apps have changed the way we direct ourselves in a city. For most of us, using a smartphone to map the quickest way to a restaurant, a show or a meeting has become a habit. Furthermore, we tend to forget how recently digital mapping has emerged in our lives. Launched in 2005, Google Map has already mapped 28 million miles of roads. It has imposed itself as the most popular digital mapping app as 77% of smartphones users regularly use navigation apps, and 70% of smartphone owners use Google Maps most frequently.

Singhal’s quote, however, echoes far back in time. Throughout history, humans have constantly tried to map their world: the quest for a perfect representation of our physical environment is not new. In the antiquity, Greek astronomer Ptolemy‘s interpretation of a “perfect” map placed the Mediterranean Sea at the centre, as every culture beyond those borders was seen as barbaric. In the Middle Ages, European Maps put less emphasis on scientific evidence and enhanced religious meanings. Later, after the discovery of the new world, Gerard’s Mercator’s famous projection stretched the poles to unrealistic proportions – the commerce at the time was from East to West and Mercator made representation choices in accordance with the interests of his time.

All these historical maps were aligned with the technological capabilities, as well as the political and social context of their times. They all claimed to be “perfect” whilst reflecting the hopes and fears of their audience. As Mark Graham puts it: “There is no such thing as a true map, every single map is a misrepresentation of the world, every single map is partial, every single map is selective. And every single map tells a particular story from a particular perspective”. Digital maps are not an exception to this rule.

The emergence of digital tools has opened up mapmaking possibilities to new levels as it allows the superposition of several layers of data on the same map. It combines real time information to geographical data. The software behind the compilation of the data is called the “Deep Map”. It is a hidden, more complex map, containing the logic of places such as traffic conditions, speed limits and no-left turns. The cartographic historian Jerry Brotton, compares the transformation from physical maps to Geographical Information Systems to a jump from “the abacus to the computer”.

The difference today is that mapmakers are algorithms and all of us individually are at the centre of the map. As the digital world evolves, where you are looking has become almost as important as what you are looking for. Consequently, Google maps uses all the available data and make it relevant to you while using your activity and location to improve its data base and algorithm. When searching on digital mapping platforms, algorithms gives a selected set of permutations from its index and it makes the selection based on individual’s search history and language used. You and your friend might come across two completely different interpretations of your cities.

The real question to be asked is: who has control over the different filters that are increasingly shaping the way we look at our world? How are their values and interests impacting our lives?

According to Brotton, Google Maps is “perfect” in the present time for “maximising online profits”. In a world driven by efficiency, individualism and profitability, the digital geographical space becomes an ideal ground to promote trade and advertising. Google maps projects an accurate image of the modern global economy in the age of big data and social media.

The problem is that we don’t intuitively question maps, and it is hard to spot the bias in cartography. Google Maps displays information in a way that suggests accuracy and trust and it is heavily influencing what we know and how we move around a city. When it suggests the “fastest route” to get somewhere, we are very likely to take it without questioning it.

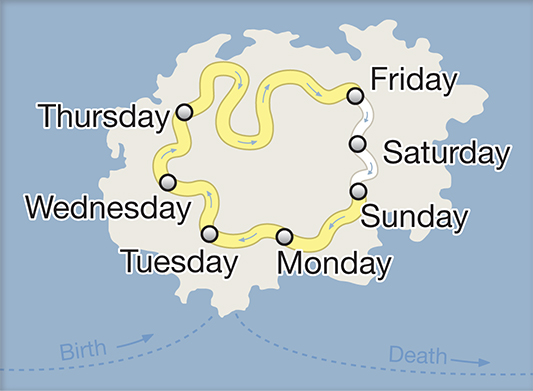

That is what map researcher Daniele Garcia wants us to do: challenge the idea of the “single-path” in our daily lives. The app only considers a few ways to go from A to B, and it has the power to make them the definitive directions to destination. In his Ted Talk, Garcia explains how he creates alternative maps emphasising different elements in a route such as nature, security or history to contrast with Google’s “efficiency filter”.

But Google Maps’ power goes beyond influencing the way we see the world, it is also shaping reality. For example, it has to certain extent some influence in establishing borders. In 2010, Google map almost caused an international conflict as it misplaced the border between Nicaragua and Costa Rica. In recent years, Google has been renaming places around the globe, considerably impacting the identities of entire neighbourhoods. That is what happened to a district in San Francisco, now popularly known as the East Cut.

Google’s biggest real world impact is on the globe’s commercial landscape. As Matt Zook put it: “There is a huge power within Google Maps to just make some things visible and some things less visible”. One of its new features, called “areas of interest”, shows the highest concentrations of restaurants, bars and shops in a given area. Not only is it enhancing Google Maps’ commercial interface but also influencing the places that will be most visited by people and thus the commercial activities..

However, information is not spread equally on the Internet and Google gets a lot of things wrong from the real streets. For example, Google data base contains 100 time more indexed information per person in Scandinavia than in the Middle-East and Tokyo’s geospatial data is greater than the African continent.

But what about the ones that stay out of the loop? Indeed, there are some worrying consequences of being invisible on Google Maps. Ask New York florist Greg Psitis, he got his shop “closed” on Valentine Day on Google Maps and lost what should have been his busiest day of the year. In the US, 19% of small businesses are invisible on the internet and a lot of them are not aware of the consequences of this modern form of anonymity. But the truth is: an inefficient digital footprint will increasingly cause real world losses, especially when you know that 97% people searching online act on the result. If you are not on the map, do you even exist?

Google Maps and more broadly digital mapping services have made moving around and traveling so much easier. Some even argue that is it easier to wander around and “get lost” now as at the end of the day you know you’ll be able to get home. However, there is a legitimate concern to be raised when the filters we almost exclusively use are chosen by a few big high-tech companies.